Introduction

A number of people have been asking for the BDRA/BAG’s views on what kind of development we think most appropriate if some or all of the proposed sites do eventually go ahead. This article outlines a top-level view of what we believe to be appropriate. It includes both praise and criticism of Basildon Council.

How We Got Here

Before looking into the detail, it’s worth a quick look at how we got here.

Basildon is building far more homes than local people need or that we believe it has to. The Green Belt around Billericay is being disproportionately targeted for political and financial reasons - developers will be contributing a lot more to Council coffers for their sites around Billericay.

Whilst the impact of this scale of development has been given some consideration on some sites, the cumulative impact across Billericay, Basildon borough and south Essex as a whole has had little credible consideration.

We sometimes hear it suggested that hyper-supply will address the affordability problem, but ‘supply and demand’ work at a regional level, hyper-supply here will do little if anything to improve affordability and simply attract well-heeled Londoners to the new houses; these new residents would commute to London at an even higher rate than the existing Billericay population.

South Essex is not a sensible place to meet the wider housing need and the type of houses delivered is at least as important as the number built when looking at affordability issues. Please take a look at this report that explores the issues in south Essex in more detail. Commuter Infrastructure - Road and Rail

We accept that commuting and housing needs could change post COVID-19 when we get to the ‘new normal’ but the fact remains that the focus on development in south Essex is disproportionate to local needs and of questionable sustainability.

Basildon is building far more homes than local people need or that we believe it has to. The Green Belt around Billericay is being disproportionately targeted for political and financial reasons - developers will be contributing a lot more to Council coffers for their sites around Billericay.

Whilst the impact of this scale of development has been given some consideration on some sites, the cumulative impact across Billericay, Basildon borough and south Essex as a whole has had little credible consideration.

We sometimes hear it suggested that hyper-supply will address the affordability problem, but ‘supply and demand’ work at a regional level, hyper-supply here will do little if anything to improve affordability and simply attract well-heeled Londoners to the new houses; these new residents would commute to London at an even higher rate than the existing Billericay population.

South Essex is not a sensible place to meet the wider housing need and the type of houses delivered is at least as important as the number built when looking at affordability issues. Please take a look at this report that explores the issues in south Essex in more detail. Commuter Infrastructure - Road and Rail

We accept that commuting and housing needs could change post COVID-19 when we get to the ‘new normal’ but the fact remains that the focus on development in south Essex is disproportionate to local needs and of questionable sustainability.

The Four Firsts Charter

|

The Billericay District Residents Association (BDRA), of which we’re part, released the The Four Firsts Charter last year, so in this article we’ll explain how we might like to see these applied – how these would shape the type of development we think most appropriate.

A copy of the Charter can be found on the Home page on this site. |

Affordable First

Local First Infrastructure First Environment First |

We’ll discuss how we would like to see them addressed through the prism of specific Policies. Such Policies are the heart of the Local Plan. In effect they set out the rule book for future development, defining much more than just where houses can be built. It is therefore important that these Policies are clear, appropriate and will be adhered to.

Many are unaware, but the BDRA scrutinises every planning application, and comments on the more important ones, in order to try to influence planning decisions. This becomes all the more important as whole estates are planned - we will strive to ensure that the Council upholds the better Policies in whatever form of Local Plan is eventually adopted.

Many are unaware, but the BDRA scrutinises every planning application, and comments on the more important ones, in order to try to influence planning decisions. This becomes all the more important as whole estates are planned - we will strive to ensure that the Council upholds the better Policies in whatever form of Local Plan is eventually adopted.

What Developers Want

Building companies are businesses, their primary concern is profit. Strong, crystal clear policies are required to rein them in, and mitigate the impact of any new Green Belt developments.

Developers would prefer to build four and five bedroom houses, to attract well-off Londoners seeking to exchange some of the hefty equity on their London homes for a larger new home in the Commuter Belt.

They’re not concerned about the quality of life of the old and new members of the community as long as their product sells. They would prefer not to deliver much in the way of transport or social infrastructure or give money to the local authority to do so. They would rather not deliver much on-site open space or build affordable homes. They will build slowly; to keep their costs down, avoid any impact on sale price, and so maximise their profit margins.

Unfortunately, while the Local Plan has some good Policies on affordability and housing mix, the provisions around infrastructure and the environment are very weak, and their vagueness means that even these weak requirements will often be delivered late, or not at all.

We have heard Basildon’s Planning Officers tell people that good design can be assured at the planning application stages. This is misguided as Basildon’s Plan “bakes in” bad design; it is extremely difficult for even a well intentioned developer to comply with Plan and deliver good design. We have to get the Plan right to give good design a chance.

Developers would prefer to build four and five bedroom houses, to attract well-off Londoners seeking to exchange some of the hefty equity on their London homes for a larger new home in the Commuter Belt.

They’re not concerned about the quality of life of the old and new members of the community as long as their product sells. They would prefer not to deliver much in the way of transport or social infrastructure or give money to the local authority to do so. They would rather not deliver much on-site open space or build affordable homes. They will build slowly; to keep their costs down, avoid any impact on sale price, and so maximise their profit margins.

Unfortunately, while the Local Plan has some good Policies on affordability and housing mix, the provisions around infrastructure and the environment are very weak, and their vagueness means that even these weak requirements will often be delivered late, or not at all.

We have heard Basildon’s Planning Officers tell people that good design can be assured at the planning application stages. This is misguided as Basildon’s Plan “bakes in” bad design; it is extremely difficult for even a well intentioned developer to comply with Plan and deliver good design. We have to get the Plan right to give good design a chance.

Before we get into the Four Firsts themselves, let’s look at two key aspects that define developments at the highest level.

Housing Densities

Housing density is important as it largely dictates how much space is left for everything else once the houses are built, such as open and green spaces, and supporting infrastructure. Typically, the denser the development the more built up it will be. In the Local Plan the expected density is part of the Policy for each individual site and it can vary across sites.

Density of homes (dwellings per hectare or dph) can mean two things:

• Density of homes across the whole site – including areas kept as playgrounds or other open space (Gross density)

• Density of homes in only the built-up parts of the development (Net Density)

The parts of the Plan setting out required densities fails to specify which type of density is meant - it is therefore open to abuse by developers. So, in this section we will describe our views on density within the developed areas only (Net Density) – we discuss our view on the extent of public open space (known as ‘green and blue infrastructure’) further on.

The required density of 35 per hectare (14 per acre) for all the sites in Billericay is pretty dense for edge of town settlements and we are concerned that it will not leave enough room for parking or street trees.

However, we’re cautiously supportive, we think good design may be compatible with such a density. While there is undoubtedly a downside, the benefits are:

• Encourages delivery of the one and two bedroom dwellings most needed by local people.

• Smaller property footprints mean homes tend to be more affordable.

• Less waste of space means less Green Belt is needed to deliver any chosen Housing Target.

By way of a reference – the recent Bell Hill Close development was built at around 35 dph, while the older parts of Noak Bridge delivered more than 40 dph through the use of terraced housing and a high proportion of one and two bed homes. Both developments have clear strengths and weaknesses.

Density of homes (dwellings per hectare or dph) can mean two things:

• Density of homes across the whole site – including areas kept as playgrounds or other open space (Gross density)

• Density of homes in only the built-up parts of the development (Net Density)

The parts of the Plan setting out required densities fails to specify which type of density is meant - it is therefore open to abuse by developers. So, in this section we will describe our views on density within the developed areas only (Net Density) – we discuss our view on the extent of public open space (known as ‘green and blue infrastructure’) further on.

The required density of 35 per hectare (14 per acre) for all the sites in Billericay is pretty dense for edge of town settlements and we are concerned that it will not leave enough room for parking or street trees.

However, we’re cautiously supportive, we think good design may be compatible with such a density. While there is undoubtedly a downside, the benefits are:

• Encourages delivery of the one and two bedroom dwellings most needed by local people.

• Smaller property footprints mean homes tend to be more affordable.

• Less waste of space means less Green Belt is needed to deliver any chosen Housing Target.

By way of a reference – the recent Bell Hill Close development was built at around 35 dph, while the older parts of Noak Bridge delivered more than 40 dph through the use of terraced housing and a high proportion of one and two bed homes. Both developments have clear strengths and weaknesses.

Housing Mix

Housing mix is just as important as housing density as it defines the sort of housing that should be built.

Developers prefer to build large homes, but there is a greater local need for one and two bedroom houses – so we’re very pleased that the Council will require that 40% of houses are one and two bedroom houses. This applies to all sites in the Local Plan under Policy H25.

It is interesting to note that the recent Redrow planning application for the land at Mountnessing Road sought to meet that requirement by building two-bedroom houses, with no one-beds at all. So, there’s a case that the Council should improve this policy to require a minimum number of one-bedroom dwellings.

The Council, to its further credit, also requires another 40% of dwellings are 3-bed, ideal for young families, meaning that just 20% are for be greater than 3 bedrooms.

We believe this to be a key policy as it will hopefully deliver the right houses for those starting out on the property ladder or for young families wanting to move up the ladder.

Developers prefer to build large homes, but there is a greater local need for one and two bedroom houses – so we’re very pleased that the Council will require that 40% of houses are one and two bedroom houses. This applies to all sites in the Local Plan under Policy H25.

It is interesting to note that the recent Redrow planning application for the land at Mountnessing Road sought to meet that requirement by building two-bedroom houses, with no one-beds at all. So, there’s a case that the Council should improve this policy to require a minimum number of one-bedroom dwellings.

The Council, to its further credit, also requires another 40% of dwellings are 3-bed, ideal for young families, meaning that just 20% are for be greater than 3 bedrooms.

We believe this to be a key policy as it will hopefully deliver the right houses for those starting out on the property ladder or for young families wanting to move up the ladder.

Affordable First

The Local Plan Policy H26 requires 31% of houses to meet the government’s definition of affordable – that they are discounted 20% from the market rate. These houses won’t be available on the general open market, but bought by Housing Associations and either offered at reduced market rents or purchase via shared ownership – often with key workers getting priority.

We are supportive of this policy; it’s far from perfect, and in the 2014 draft plan it was a much better 35%, but it’s hard to see how the Council could do much more. However, the prices for homes available under the affordable housing definition will still be very high - three bed houses in Gardiner’s Lane Basildon are going for £400,000, on Roman Way in Billericay for £440,000 while similar houses in Dry Street Basildon are selling for over £500,000, so new homes in Billericay will be sold for eye-watering rates, even when classified as ‘affordable’.

The Council is endeavouring to accelerate its development of truly affordable Council houses, but, with the best will in the world, they will only be able to deliver a relatively modest number – almost certainly none of them in the sites released from the Green Belt around Billericay.

We are supportive of this policy; it’s far from perfect, and in the 2014 draft plan it was a much better 35%, but it’s hard to see how the Council could do much more. However, the prices for homes available under the affordable housing definition will still be very high - three bed houses in Gardiner’s Lane Basildon are going for £400,000, on Roman Way in Billericay for £440,000 while similar houses in Dry Street Basildon are selling for over £500,000, so new homes in Billericay will be sold for eye-watering rates, even when classified as ‘affordable’.

The Council is endeavouring to accelerate its development of truly affordable Council houses, but, with the best will in the world, they will only be able to deliver a relatively modest number – almost certainly none of them in the sites released from the Green Belt around Billericay.

Local First

This aspect of the charter can be said to apply to the need to moderate the boroughs own Housing Target (local needs are 9,600 compared to Local Plan Housing Target of 15-20,000) and also applies to the type of housing, as already described.

It also applies to the how as well as a what, seeking to ensure that the needs of the existing community are considered when considering changes to road layouts, the nature and location of any new facilities and any other aspect of urban design that arises when the detailed design of the estates are brought forward.

A good example is flooding – the developments at Kennel Lane, Frithwood Lane and elsewhere pose a direct threat to existing nearby properties.

Sadly there is no formal Policy in the Local Plan that directly meets the need for Local First, or adequately mitigates the potential damage on the existing areas from new development.

It also applies to the how as well as a what, seeking to ensure that the needs of the existing community are considered when considering changes to road layouts, the nature and location of any new facilities and any other aspect of urban design that arises when the detailed design of the estates are brought forward.

A good example is flooding – the developments at Kennel Lane, Frithwood Lane and elsewhere pose a direct threat to existing nearby properties.

Sadly there is no formal Policy in the Local Plan that directly meets the need for Local First, or adequately mitigates the potential damage on the existing areas from new development.

Infrastructure First

The Foreword of the Local Plan proclaims that it is an “Infrastructure First” Plan, and politicians of all parties parrot this line – some of them believe it.

It’s an empty claim; the wording of the plan is such that the paltry infrastructure changes referred to are rarely a pre-requisite to development or indeed formally linked in any way. They are often also uncosted and unfunded. The developers will have the go ahead to build, but the Council will struggle even to get them to deliver the already woefully inadequate infrastructure requirements.

There are some vital elements of infrastructure that is impossible for the Council, and even central government, to deliver – other aspects might only be addressed through the South Essex Plan – and that hasn’t been written yet. It is impossible for the Plan to deliver the necessary changes to the railways or A127 in the plan period, or probably ever. The government keeps talking about “40 new hospitals” – but we haven’t heard of anyone lobbying for one in South Essex.

We need the Plan improved to make sure it both identifies and delivers more of the social, transport and other infrastructure that it is in the Councils power to require – and to do that it needs to close the many loopholes.

It’s an empty claim; the wording of the plan is such that the paltry infrastructure changes referred to are rarely a pre-requisite to development or indeed formally linked in any way. They are often also uncosted and unfunded. The developers will have the go ahead to build, but the Council will struggle even to get them to deliver the already woefully inadequate infrastructure requirements.

There are some vital elements of infrastructure that is impossible for the Council, and even central government, to deliver – other aspects might only be addressed through the South Essex Plan – and that hasn’t been written yet. It is impossible for the Plan to deliver the necessary changes to the railways or A127 in the plan period, or probably ever. The government keeps talking about “40 new hospitals” – but we haven’t heard of anyone lobbying for one in South Essex.

We need the Plan improved to make sure it both identifies and delivers more of the social, transport and other infrastructure that it is in the Councils power to require – and to do that it needs to close the many loopholes.

Environment First : Green & Blue Infrastructures

The environmental considerations include bio-diversity, landscape and accessibility. This article won’t cover issues around air pollution and moving towards a carbon-neutral future – important as these topics are.

According to national planning regulations (the NPPF), developments are, in theory at least, meant to deliver a net improvement in bio-diversity. At first sight a contradiction in terms, this ideal is sometimes possible.

The best way to do this is via the approach to gross density which we’ve already referred to – if sites have a high proportion of “green and blue infrastructure” (open spaces and water features) then an improvement in biodiversity can in some cases be achieved. There are Council policies which require a fairly modest 38% of a site to be open space, however, the submitted Basildon Local Plan appears to override this requirement and does not appear to define this or any other proportion on a site to be open space. As a result dense built-up estates are possible and that will suit developers as there is no profit in open areas.

Unfortunately, the way the Local Plan is written means that this net improvement probably can’t be delivered in any of the Billericay sites - even if the developers were sympathetic, though for some sites, a net increase in biodiversity might be possible if more open space were provided.

The Kingsbrook development near Aylesbury (https://www.kingsbrook-aylesbury.co.uk/) is a good example of what can be achieved, 66% of the total area is given over to Green and Blue infrastructure.

According to national planning regulations (the NPPF), developments are, in theory at least, meant to deliver a net improvement in bio-diversity. At first sight a contradiction in terms, this ideal is sometimes possible.

The best way to do this is via the approach to gross density which we’ve already referred to – if sites have a high proportion of “green and blue infrastructure” (open spaces and water features) then an improvement in biodiversity can in some cases be achieved. There are Council policies which require a fairly modest 38% of a site to be open space, however, the submitted Basildon Local Plan appears to override this requirement and does not appear to define this or any other proportion on a site to be open space. As a result dense built-up estates are possible and that will suit developers as there is no profit in open areas.

Unfortunately, the way the Local Plan is written means that this net improvement probably can’t be delivered in any of the Billericay sites - even if the developers were sympathetic, though for some sites, a net increase in biodiversity might be possible if more open space were provided.

The Kingsbrook development near Aylesbury (https://www.kingsbrook-aylesbury.co.uk/) is a good example of what can be achieved, 66% of the total area is given over to Green and Blue infrastructure.

Figure 1. Two-thirds of the Kingsbrook development in Buckinghamshire is given over to 'Green and Blue infrastructure'.

According to Essex County Council’s “Garden Community” principles, Garden Communities should provide a minimum of 50% Green and Blue infrastructure. Garden communities are a minimum of 1,500 houses in scale, so shouldn’t the south-west Billericay developments (at least 1,700 houses) be treated as a Garden Community and so have more than 50% open space? And if we’re ambitious to achieve good design, then we ought to apply this principle to the smaller sites? The requirement for a net improvement to biodiversity still applies after all.

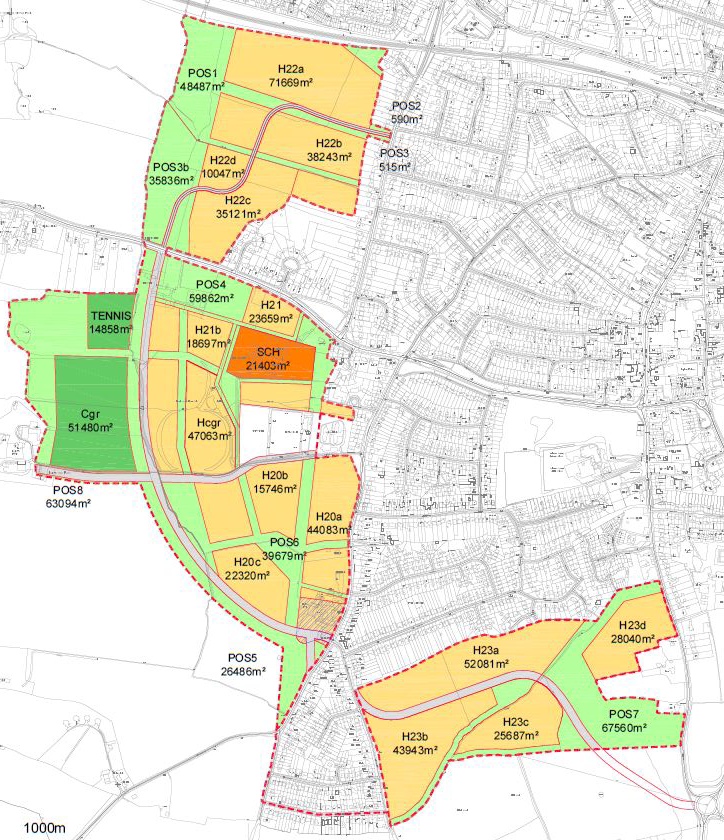

Figure 2. The 2017 Framework for development in South-west Billericay. The poor open space provision is based on needs of underground pipelines and narrow corridors for existing rights of way. Since 2017 the density has increased from 30 to 35 dwelling gs per hectare so less space should be required for the same number of homes meaning slightly more green space might be provided than shown on this map. But conversely more houses could be built in the same space reducing green space provision! Note - since this drawing was produced the proposed location of the cricket ground on the left has changed.

There are weak commitments in the Local Plan to very modest levels of open spaces, much of this is likely to be scraps from the table, narrow strips of green alongside a busy and oppressive ‘Relief Road’ or strips of grass following the course of sensitive oil and gas pipelines.

Figure 3. Open Spaces would include as strip of green on the far side of the busy Relief Road

Our attractive well used rural rights of way seem likely to be reduced to little more than alleyways, cut across by major and minor roads, and boxed in by garden fences. The development at Greens Farm Lane has fundamental flaws, but at least it seeks to deliver a nature reserve.

Figure 4. Many of the open spaces will be little more than alleyways: current rights of way or pipeline routes, ill-suited for tree planting and of limited community use.

But if we’re to have 50%+ open space, how should it be laid out?

Highly sensitive sites like woodlands and other rural areas recognised by specific designations should be protected by significant buffers, and their value enhanced through appropriate management, and in some cases by changes of ownership, or by extending the habitat.

Within sites, we would like to see Public Rights of Way, trees and hedges, ponds and watercourses used as the basis of a generous ‘Green Grid’ of open spaces within the site. Play areas, parkland, sports pitches, allotments, flood attenuation ponds and nature promotion/protection areas would be built around that Green Grid framework. Where possible we should also seek agreements for new rights of way from new developments into the wider rural Public Right of Way Network.

Broad public open-spaces around both banks of watercourses provides more than a pleasant open space, there are a number of measures that can be used to prevent flooding (on-site, in neighbouring properties and downstream) that are also fantastic at promoting bio-diversity:

• Tree planting

• Re-channelling the brooks to provide a longer more sinuous course.

• Provision of attenuation ponds to slow run-off and provide habitat.

It’s important to have significant open space within sites, but there can be value in also providing a block of land on the new urban-rural boundary, or even on a site some distance away - it all depends on the specific qualities, constraints and opportunities that apply to the site being developed.

Finally, the developed areas can be designed with nature in mind – we would like to see significant number of street trees – many of them large, many of them native trees which tend to be more valuable for wildlife.

The homes and gardens themselves can be developed according to provide opportunities for wildlife, swift bricks, bat boxes, hedgehog-accessible gardens and so on. There should be Plan Policies requiring this, and proper enforcement to ensure it is actually delivered.

Highly sensitive sites like woodlands and other rural areas recognised by specific designations should be protected by significant buffers, and their value enhanced through appropriate management, and in some cases by changes of ownership, or by extending the habitat.

Within sites, we would like to see Public Rights of Way, trees and hedges, ponds and watercourses used as the basis of a generous ‘Green Grid’ of open spaces within the site. Play areas, parkland, sports pitches, allotments, flood attenuation ponds and nature promotion/protection areas would be built around that Green Grid framework. Where possible we should also seek agreements for new rights of way from new developments into the wider rural Public Right of Way Network.

Broad public open-spaces around both banks of watercourses provides more than a pleasant open space, there are a number of measures that can be used to prevent flooding (on-site, in neighbouring properties and downstream) that are also fantastic at promoting bio-diversity:

• Tree planting

• Re-channelling the brooks to provide a longer more sinuous course.

• Provision of attenuation ponds to slow run-off and provide habitat.

It’s important to have significant open space within sites, but there can be value in also providing a block of land on the new urban-rural boundary, or even on a site some distance away - it all depends on the specific qualities, constraints and opportunities that apply to the site being developed.

Finally, the developed areas can be designed with nature in mind – we would like to see significant number of street trees – many of them large, many of them native trees which tend to be more valuable for wildlife.

The homes and gardens themselves can be developed according to provide opportunities for wildlife, swift bricks, bat boxes, hedgehog-accessible gardens and so on. There should be Plan Policies requiring this, and proper enforcement to ensure it is actually delivered.

Conclusion

The Local Plan would further overdevelop the whole borough; it includes too many houses, many of which have been pushed to highly unsuitable locations around Billericay due to political and financial considerations.

BDRA-BAG will continue to contest the fundamentals of this proposed Local Plan and are preparing for the Examination in Public in front of the government appointed Inspector. If parts of all of this are passed then we will use the Four Firsts Charter as a framework to influence the nature of the housing delivered.

The Local Plan does provide some good policies on the types of housing delivered – including affordability, and if the Local Plan is adopted in the current form, we will, at each planning application, lobby the Council to enforce the rules, and checking that the developers actually build what is required.

While there are some good aspects to the Local Plan, the provisions around infrastructure and the environment are very weak.

Worse still - the Councils failure to meet the governments ill-conceived “Housing Delivery Test” means it may lose its power to influence the policies that seek to shape developments in its Local Plan. This would have a highly adverse effect on the borough.

We have always argued that for an authority like ours, one that is lucky enough to have Green Belt protections, that “No Plan is better than a Bad Plan”.

This bad Local Plan is now therefore worse than it has ever been – we believe the Council should exercise its right to withdraw the Plan.

If the Local Plan is redrafted, then the Council should require that any sites remaining in its Plan should have a detailed, but not necessarily lengthy, Masterplan. Some of these probably already exist – but have not been shared. Newly required Masterplans would be included in future consultations and would improve the effectiveness of the plan by detailing the costing, funding, phasing and location of the transport, social and environmental infrastructure so vital in ensuring the Local Plan does not remain a bad Local Plan.

BDRA-BAG will continue to contest the fundamentals of this proposed Local Plan and are preparing for the Examination in Public in front of the government appointed Inspector. If parts of all of this are passed then we will use the Four Firsts Charter as a framework to influence the nature of the housing delivered.

The Local Plan does provide some good policies on the types of housing delivered – including affordability, and if the Local Plan is adopted in the current form, we will, at each planning application, lobby the Council to enforce the rules, and checking that the developers actually build what is required.

While there are some good aspects to the Local Plan, the provisions around infrastructure and the environment are very weak.

Worse still - the Councils failure to meet the governments ill-conceived “Housing Delivery Test” means it may lose its power to influence the policies that seek to shape developments in its Local Plan. This would have a highly adverse effect on the borough.

We have always argued that for an authority like ours, one that is lucky enough to have Green Belt protections, that “No Plan is better than a Bad Plan”.

This bad Local Plan is now therefore worse than it has ever been – we believe the Council should exercise its right to withdraw the Plan.

If the Local Plan is redrafted, then the Council should require that any sites remaining in its Plan should have a detailed, but not necessarily lengthy, Masterplan. Some of these probably already exist – but have not been shared. Newly required Masterplans would be included in future consultations and would improve the effectiveness of the plan by detailing the costing, funding, phasing and location of the transport, social and environmental infrastructure so vital in ensuring the Local Plan does not remain a bad Local Plan.